Issue 11 Foreword

For the past year, time has been falling through my hands like hose water. I moved from Iowa City to Denver to begin a PhD program, which quickly took over my life, my body, my consciousness, my time. It feels like a blink of an eye ago that I was sitting in my then-empty apartment, which I have since filled with the signs of my life, finishing the foreword for Issue 10 in July 2022. Here I am, a year later, penning the Issue 11 foreword. As such, I want to begin this introduction with a sincere apology. I wasn’t able to sustain the bi-annual publishing calendar that I aim for with Guesthouse in 2022–2023, and I wasn’t as communicative with our audience and contributors as I should have been. I so appreciate the grace and patience that has been extended to me by all of you, our fans and readers. And by our fantastic contributors, who have waited a long time to share these 30 pieces of visual and literary art with you. I also want to thank my readers and editorial team, especially Harrison Cook, as well as the Issue 11 production editors, Olivia Muenz and Nat Raum, who stepped in to help finalize this issue at the eleventh hour. It is my true hope and dogged goal that our 2023–2024 season will get us back on track, with Issue 12 forthcoming in December 2023. There is so much goodness ahead. Thank you for sticking with us — and for being here now.

It is my pleasure to discuss the marvelous work you will find in these pages, beginning with Lauren Green’s poem, “Lisbon,” a poem that ties a tentative knot between present and past. Green’s speaker evokes her grandmother “in her dressing gown, remembering / the days, how they shook and lingered /over the calçada. [...] Between us, a portal wends / like a crack in a windshield.” From this crack in the continuum, Green can merge her speaker’s subjectivity with that of her grandmother’s: “How still / we must stay while waiting [...] for our father’s voice to drop down,” she writes, “a rope that frays instantly to flame.” “Our father,” of course, evokes the presence of a religious figurehead, but it also blurs the line that differentiates the generations. Similarly, Monika Cassel’s “Great Uncle Carl-Christian (b. 1903) With Stag” begins in family history, with a photograph: the titular character standing in the woods. “The rifle’s / leather band, slung round his shoulder, gleams. [...] Stretched out / across the frame, the stag lies at his feet.” The speaker, from her present vantage, knows what will unfold in the decades this young man will soon live through; the violence in the photo becomes prescient, knowing, a symbol of darkness, hubris. “How long still will that future bend to his imagining?” the speaker asks. History and memory become malleable in the poem’s last moment: “That can’t be my father, my aunt says, peers at the photo print. / He’d never make a kill that messy, or pose with it.” Evan Nicholls’ suite of poems pairs well with Cassel’s, as it looks closely at idioms in English that have to do with guns and gun violence. In “Gun Down,” Nicholls writes, “The gun fell into the lake. The gun fell onto the scaffold. The gun fell for the trombone. It was a meet-cute. The gun fell over. The gun fell like a crutch almost every night.” By analyzing the language of guns, and by recontextualizing, destabalizing, literalizing this language, Nicholls challenges us to think of how violence exists in and across language.

“Calçada Portuguesa – Portuguese Calcada – or mosaic (also known in Brazil as Portuguese stones) is a specific pavement, used mostly for finishing the walkways and sidewalks, alleys, squares and other bustling places.” (source)

Kirstin Allio’s poem, “My Mother Named,” a piece about early influence and becoming, is one of several in Issue 11 that speak to experiences of gender. A response to and reframing of Genesis, it recalls two women from the speaker’s young life: her mother, whose “concern tends / Toward unyielding,” and a third-grade teacher, who exposes her to the story of Adam and Eve. “How could the boys / Look at us the same way again?” she asks after hearing the story of Eve. A bildungsroman, it shows how the speaker came to understand herself in the world: named, and thus, dangerous; embodied, and thus, in danger; “brightening,” “molten.” A similar complexity exists in Jai Hamid Bashir’s poem, “A Pornography,” which conjures, as its extended metaphor, the oyster. “I know you can persuade an oyster / into creating,” she writes. “[A] false / center is created, then a pearl emerges from / a swarming of flesh.” Such is one of many “scarabs of vivid womanhood” in the poem — images that build into the prophetic suggestion that “there is a protected body inside every armor,” a pearl, ripe for harvest. Pear, wasp, oyster, canary. Each of these bodies take and are taken from. Thus, the beauty of the body becomes vulnerable, violent, powerful. “Ma would then hand me the paring / knife: skin this perfectly; it is part of being / beautiful.”

We are proud to present Vivian Davis’ first published poem, “Shame,” which uses a tilted, off-kilter diction to express how shame is created, held, and endured in the body and consciousness. “Shame, you / copper rank torch trumpet. Bald rash like swamp / soap.” Davis’ language is all askew, deliciously ghastly, off-kilter, too big, too heavy. “My sister / calls it all bull shark,” she writes,” but I’ve watched her cram it / down her own brash bucket from tank to toad. She sham / wheels the bat scream with the best of us.” “Shame” never subjects its reader to nonsense, always just skirting the fine line. As such, this is a finely wrought poem that offers a language of the body, a language of the shamed, the shameless. Shame is also at play in Jessica McCaughey’s essay, “The Pump,” a no-holds-barred look at the realities of postpartum life and the challenges she faced breastfeeding her newborn. “The baby screams as if she is in excruciating pain at night when she wakes, hungry,” she writes, accounting her daughter’s first few weeks of life. “It takes us three or four minutes to go heat up her bottle of refrigerated, pumped milk. I attach myself to the pump every two hours, 24-hours a day for approximately a half hour at each session.” Her painful and honest reflections bravely reveal parts of motherhood that are often shrouded in stigma and shadow, normalizing experiences that childbearing people face every day.

Freshwater oyster with pearls. (source)

Littered beach. Photo: Mario De Moya F. (source)

Four poems in Issue 11 profoundly engage with the landscape. Beverly Burch’s poem, “Destroyed Sonnets,” is a pair of stanzas that mirror one another –– the first line of section one becomes the last line of section two, and so on. As the second section musses up the language of the first, retooling and re-angling it, the poem enacts a kind of destruction, a stomping on, a burning down. It is apt, considering the scene the poem evokes: a group of people trampling a beach ecosystem with no regard for the consequences of their actions: “Tourists they are, crossing salt marshes to get to beach, / giants treading delicate flora, whooping laughter / like children on holiday. What’s a jeweled snake / [...] to party-goers?” Likewise rooted in a sense of place, Tommy Archuleta’s selection of poems “from Fieldnotes,” demonstrates how grief fragments reality, family, landscape. Located distinctively in the western United States, these poems oscillate between lushness and barrenness. “Some nights her name / comes bounding down the canyon,” he writes, speaking of the late beloved, “its music known to root / you stories deep.” These are poems of the left-behind and the ongoing, and they speak to the profundity of speaking for, and to, and of the dead. They are a ritual of remembering that cause “the eldest of the five hellebores / she had planted / the day before she died / [to] [liven] just a little.”

“View looking west across the southwestern United States, including Nevada, Arizona, and California, taken from the International Space Station, acquired on September 9, 2010.”

“Walter Vail on horseback, ca. 1898. Source: Empire Ranch Foundation archives A530-42” (source)

The typography of fernando xáuregui’s poem “Topography of the Desert” presents a spare, beautiful visual representation of its content: “tell me,” it begins, this imperative surrounded by white space, “of the desert” — and then another long visual pause. Then, later: “of what needs little” — a long pause — “rain.” It is a sparse sentence; the eye slowly traces one fragment to the next as if following a thin line across a map. Such is the “slow thirst” of the flora and fauna of the desert landscape, their “stoicism,” their strength, their survival. The environment is also at stake in Will Russo’s poem, “Theorem.” As a theorem itself — “a general proposition not self-evident but proved by a chain of reasoning” — the poem suggests that the reader follows its imaginative leaps as if following a logic. “Say, a man,” it begins. “The man is a wrangler, restraining a horse by the muzzle with rope. [...] The man has made a life of conquering. What does the horse know of control? [...] After the section break, the poem shifts, applying the same question to a much larger subject: “The wild earth bucks what’s living, wanting us off. In the desert, a tornado shreds a rift throughs unset-touched clouds.” The reader is left questioning, “What does [the world, the wild, the Earth] know of control?”

Rae Armantrout’s selection of new poems are minimal and sharp. With her signature eye for uncanniness, she observes moments of mundanity in a way that makes them seem sublime, strange, notable, poetic. In “Dots,” she writes: “Poems elongate moments. / ‘My pee is hot,’ she said, / dreamily, mildly / surprised.” In “Familiars,” “Renee calls her mask / ‘Maskie’ / and laughs / as if she were / in on / the trick / of ensoulment.” For decades, Armantrout’s poems have delighted us and challenged us to see the strange, the glimmer in the everyday, and these join that lineage. These in particular speak to the experience of the pandemic, when so many of us were hunkering down in our homes, seeing our domestic spaces in new detail. Kelly Terwilliger’s “This other life,” also looks at the domestic space, observing the minutia of her pet tortoise. “The tortoise / making his slow rounds of the house, / shuffling across the floor,” the speaker observes, “the tortoise someone else passed on to me / when they decided to get a dog.” The scene is ordinary, but the tortoise in this moment, like animals often do, evokes in the speaker an existential awareness: “Do I know what to do? Have I done it?” Seen through the filter of this smaller but no less significant life, the speaker’s own habits and patterns seem like those of a stranger.

Nathaniel Calhoun’s strange and beautiful poem, “Iditarod,” evokes a linguistic and cultural breakdown, the state of life “after an epoch where everything acted / like an urchin’s spine on a hole punch.” Although the poem makes little certain, the speaker is reckoning with wholeness and partiality — of self, of landscape, place and time. He writes, “it’s not unraveling if it wasn’t woven first. / tangled looks raveled if you’re troubled enough.” Here is a personal idiom, a message eked out on a secret frequency. Perhaps a message from the future, beyond the anthropocene. If life is an “Iditarod of self,” one must “hold on through a dog eating solar flare.” Both of Hannah Piette’s poems in Issue 11 operate in a similar way, evoking a private diction that flushes clauses sentences against one another and mismatches tenses. In “Measured For,” Piette writes, “got creative in the ditch / looking for the Roman wall / but wanted to turn back, after all / it wasn’t there / there’s only one considered second”. The motion of the mind moves quickly, and each image is both partial and whole. The reader must experience multiple sensory inputs at once.

Mark DeCarteret’s poem, “The Year I Went Without Saying the Rosary,” one in a series of poems from a manuscript in progress, “The Year I/We Went Without,” considers the failure of ritual. “I must have bought a bad batch,” the speaker suspects — or confesses. “A thousand rounds in, and I’m not sure what / sounds good anymore. Gods blur into one.” In this poem, saying the rosary, an act meant to serve as penance for the soul, is superseded by the needs of the sick body. “Maybe, if I bore down even harder, / the saints would adore me. [...] But I am too stubborn with worry to notice, be noticed.” Here, grace is transactional, something that must be constantly performed. The body that cannot perform it must go without. Robert van Vilet’s “Four Lessons” is the second poem in Issue 11 that engages explicitly with religiosity. “Through the gift of the spirit / the four lights appeared,” he writes, evoking the certainty of the scriptural metaphor. But then he asks, “What does this mean, / ‘through the gift?’” So begins the primary engine of the poem: deep questioning. “It means help is always / near but not always near / enough,” the speaker answers. But his line of inquiry is just beginning. “What does this / mean, ‘of the spirit?’” This poem wrenches apart the truisms of spirituality as well as the givens of everyday language, pushing us to think carefully about what language can, and cannot, offer us.

Poet Li-Young Lee (source)

Two poems in Issue 11 align, in some ways, with the genre of “erasure poetry,” but both featured poets reimagine the conventions of this mode in exciting ways. Mylo Lam’s two visual poems reexamine works by Thích Nhất Hạnh and Li-Young Lee. The primary conceit of an erasure poem — that a primary text has been stripped away or modified — often poses a question of “erasure” at the sociocultural level — who, or what, has been erased from what narratives, what canons, and why? Likewise, with his titles, Lam announces that these poems are experiments in “selective reading” in as much or more than they are erasures: a robotic presence, “Tri Nhan 004,” “reads” the Thích Nhất Hạnh and Li-Young Lee poems, carving new poems out of them: “And me / Am I inside you? / You’re always inside me / answered / the body / Am I inside you? I asked once / lying / confused / heart.” These poems are symphonies of multiple voices, valences, and technologies. Twila Newey’s “Blue Excavations,” a series of visual poems composed of blue watercolor paint laid over black text, which runs and drips. There is a sense of erasure in these poems, as the printed text becomes muddled, convoluted, and hidden beneath the watercolor strokes. To read these poems as “excavations,” however implies a reverse relationship between source text and original. It is as if Newey’s legible text — “What is [illegible] / :SEA / :a[n] / object / [illegible] / // prais [illegible] her fellow [illegible]” — has been excavated, like fossilized materials, from slabs of blue rock.

Diane Mehta’s “Reading Thom Gunn’s Lament” also draws from a previously published work. Having read Gunn’s poem 1995, “Lament,” (“Your dying was a difficult enterprise…”) the speaker finds themselves overcome, “oblique and shaken.” Mehta writes: “His loss was restless, no repose / for endings, intractable and cruel,” she writes, “and even then, it took me in.” Much like Gunn, who, addressing his late beloved, wrote, “And so you slept, and died, your skin gone grey, / Achieving your completeness, in a way,” Mehta observes how in the aftermath of a death, the lack, the gaping hole created by the departure, becomes a presence, a whole, a shadow self. “Isn’t it true that absence is a reticulated / presence, its shade the shadow following you?” Timothy Leo’s “Delta, Utah,” also emerges from grief. “Wish, worry, wonder — terms / the oncologist murmured at us / in the family meeting.” Dealing with a loved one’s cancer diagnosis, the speaker imagines an impending apocalypse, a “plague,” where “the pink towers / fall and the birds sing cat-cat-cat.” So begins a poem of admission: “I wanted Utah,” Leo writes. “Teresa of Ávila / wanted the spear and got it.” Then, later, “I wanted Utah, I wanted him / whole.” These dreams become the dreams of the past, and the future is replaced by the present, blinding, almost too bright to look at, “fire, god, sucking-chest-wound.”

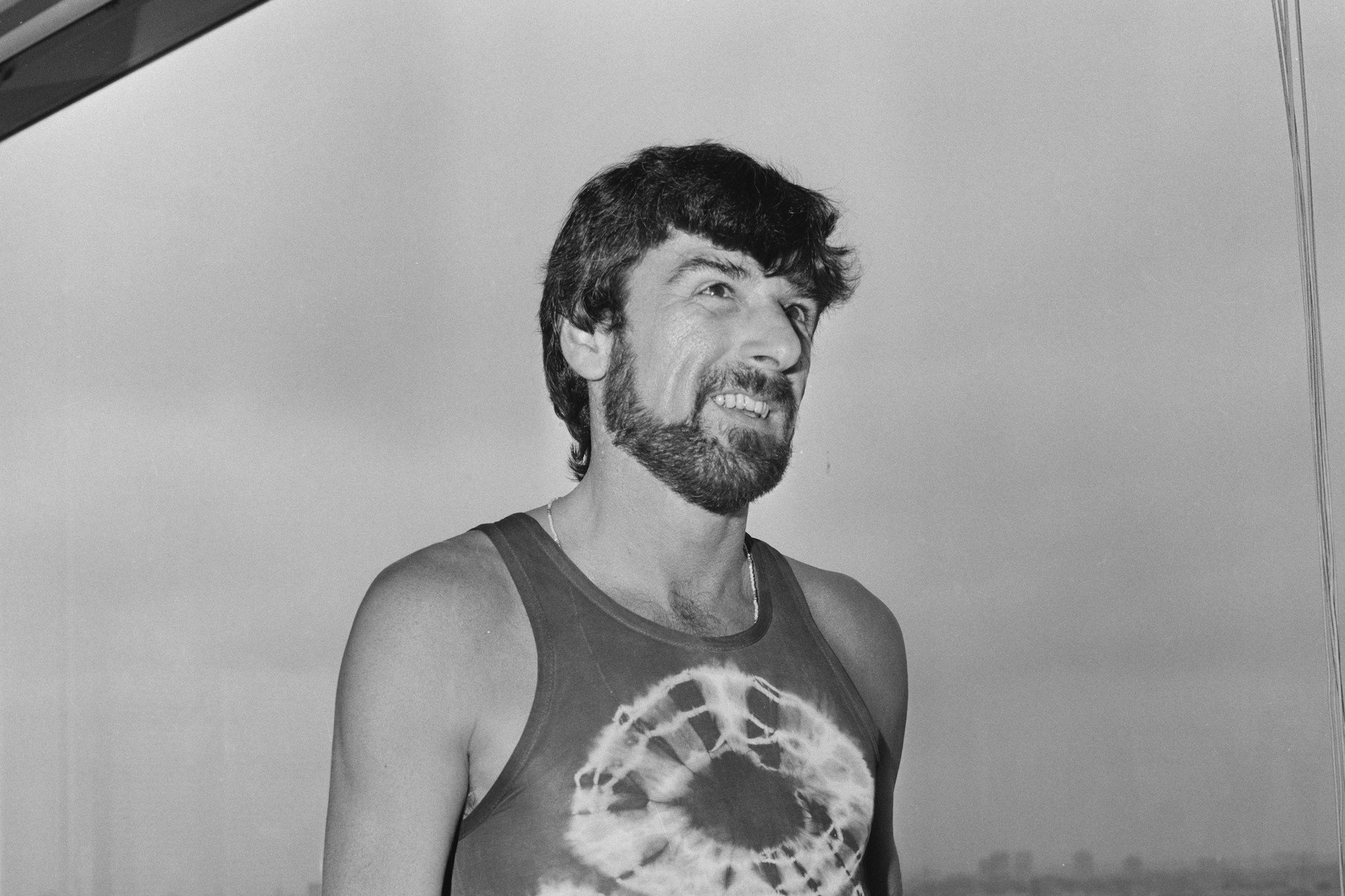

“English poet Thom Gunn (1929 – 2004) attends an event, UK, 25th June 1970. Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty images.” (source)

“The death of St. Teresa of Avila,” Giovanni Segala (Italian, 1663–1720). Oil on canvas, 1696. Church of San Pietro in Oliveto, Brescia.

Another grief poem, Dean Rader’s “Poem Begun on the Day of My Father’s Death and Completed on the Day I Dreamed of My Own,” begins in the “now-hushed,” an “overture of emptiness.” Like in Green’s poem, “Lisbon,” the speaker’s sense of life and death collapses into the memory of the departed. “how long have I waited to think a thought that was not / its shadow?” Rader asks, as if questioning the singularity of consciousness. (Recall, Mehta, above: “Isn’t it true that absence is a reticulated / presence, its shade the shadow following you?”) Then, the poem lands in the metaphysical — one remedy for the grieving body and soul: “let us conceive this life / as a corridor — [...] let us be the medium, the decussation—. Fred Schmalz’s “Man with Hat in Wind” is a truncated biography — a life reduced to a few bits of language. In the first stanza, the man performs a daily routine, “a rhythm to guard against forgetting.” He dresses, “[tucks] a phone into his pocket. [...] check stove check coffee maker grab keys.” We begin in the mundane. Stanza two zoom out, recalling how, years ago, the man was “called to the morgue to identify his colleagues.” This, then, becomes a poem about grief, about how life goes on after tragedy. Tragedy is, artfully, made mundane. “He was not saddened by the deaths we all endure,” Schmalz writes. “He had, even by the time the others drew their last breaths, sewn the loss into the fabric of his own life.” The poem ends with acceptance, release.

In Paul Shumaker’s video, “Clay Bowl,” the viewer is confronted with what appears to be a single still image. But Shumaker writes, “a clear image didn't interest me.” Shot on a camera that would help him emphasize “the surface of the screen,” the video is meant to call attention to the artifice of the genre — as well as the viewer’s instability. “Nothing, seemingly, moves during the video,” Shumaker writes. When put on film, the “stillness” of this “still life” is called into question: “what’s revealed are pulsations that originate from the camera.” It reminds me of Marina Abramović’s video “Carrying the Milk,” which likewise demonstrates an unreliable stillness. We’re lucky to have a second piece of visual art in Issue 11, Ann Weber’s sculpture, “Marie Antionette,” which is also the Issue 11 cover. Over nine-feet tall and made entirely of “found cardboard and staples,” the piece strikes a silhouette that is both feminine and jurassic. The material components of the sculpture are jagged and sharp — cardboard edges, corners, and right angles flush against one another. But the shape they compose is distinctively soft. We can see a representation of Marie Antionette, as the sculpture wears something of an eighteenth-century costume from its “waist” down, but the piece is also so distinctively non-human that the viewer must project their own interpretations and connotations onto it. Per Weber’s artist statement, “Her interest is in expanding the possibilities of making beauty from a common and mundane material.” By creating new forms from refuse, Weber reminds her viewers that meaning must always be constructed.

Still from “Carrying the Milk,” 2009, Marina Abramovic, Color video with sound, Duration: 12 min. 42 s. loop. (source)

Trompe l'oeil fish in pressed glass, c. 1870. Pressed glass, paint, wood, velvet. Unknown American artist (source)

Matthew Tuckner’s “Trompe L'oeil” enters a conversation about the transmutation of word into image. “It’s a fish because I tell you it's a fish,” he begins. (I recall, of course, the most memorable line in Faulkner, “My mother is a fish.”) “A fish that’s more like a car than a word,” Tuckner writes, “for how quickly it drives the mind to the places / it already knows it knows.” This transmutation, of word, into vehicle, into mind, into image, into recognition, becomes the “trompe l'oeil” of the poem, and as such, it becomes a statement on semiotics itself. Tucker extends the movement of the “word” into the body, (in a sense, making it “flesh) ending the poem with a personal transfiguration: “So many cherry blossoms in my veins, I must be a cherry.” This poem pairs nicely with Sylee Gore’s deceptively simple poem,“Why paint?” which answers that question, first, with irony. “I do it for the money.” Then: “Everything is found. / Painting is the glove you wear to touch a wound.” Its final gesture, which intervenes against the surety of the poem so far, is a concluding statement akin to “You must change your life” (Rilke) or “I have wasted my life” (Wright). “Why paint?” ends with: “I don’t know what I want.” This seems to be the most authentic answer to the poem’s titular question. One makes art because it is a means of seeking, of desire. Sally Keith’s poem, “Obedience,” also looks closely at the art-making impulse. “I found a little poem called ‘Obedience,’ it begins, “including a ferocious current and the pointlessness / of working against it. […] I understood / the words but for whatever reason could not bring myself / to translate it.” What follows is a wading through and against this current — river, rain, tears — and a reckoning with what they, as concepts, as signifiers, do and no not convey. Obedience to the self emerges. One’s intuition. Obedience to the original, the context of translation. Obedience to desire, the desire to tell, and the poem obeys.

Mime among pedestrians (source)

Two poems Issue 11 recall encounters with strangers. To first read Liane Tyrrel’s “Moving the Bodies” is to wonder at the literal circumstances of its opening gambit: “I was asked to move the bodies — there were just two. Left alone in small beds.” It is a blunt, unaffected statement, and at first, I expect this poem to be about carrying sleeping children out of their beds. But soon, the poem demonstrates its literalness: “I could go crazy from this work,” Tyrell’s speaker says, “moving lonely men, already dead. Sitting up in bed waiting / for nothing.” It is a poem about the work of death, of cleaning up after the dead, “visible if anyone had bothered, in passing, / to glance inside their window.” What I love most about it is that it is deeply unsentimental. We readers must also look directly into the faces and bodies of death. Jennifer K. Sweeney’s “Once I hid behind a tree and watched a mime” recalls the speaker’s encounter with a street performer in Prague, “how awkward and direct / it was to approach him, like approaching the god of my childhood at the end of a corridor.” The mime becomes a kind of mirror for the speaker’s consciousness as she passes him each day, “a homing ritual,” she calls it, “or a meditation or a foothold against the crisis / I brought with me.” The crisis remains unspoken in the poem, but it is through this unspeaking human character, “open[ing] tiny doors / in the wind,” that she comes to see herself and others more clearly, acting and reacting, making gestures.

Thank you for reading Issue 11 of Guesthouse. We’re all so glad you’re here.

Jane Huffman

Editor-in-chief